Welcome to November, and the “change of season” here on EFW. I hope you enjoyed our tour of crossing genres in fantasy. For the next few months, we’re going to explore the topic of world-building and what makes a great fantasy setting. You can look forward to some posts from our regular contributors on the topic, as well as a few guest posts from new authors I’ll be inviting onto the blog to do the World Builders 2.0 interview (here are some past posts to those not familiar with the series).

Look forward to posts on what makes a great fantasy map, how to delve into setting with world-building tools, and how-to posts on the world-building process from different writers. I hope you’re as excited as I am!

What is world-building?

World-building, also called worldbuilding, is the process of creating an imaginary world. Often this is done for the sake of exploring the underpinnings of setting and character in a fiction world, but it can extend to other areas, such as RPG gaming or even sometimes, just for fun. The term “world-building” has been around since it first appeared in the Edinburgh Review in 1820.

Naturally, to fantasy writers, world building is an enormous part of the creative process. Some writers approach it with a top-down method: build the world from broadest levels downward, working from general to specific, often times as a separate process from drafting a novel. Other writers approach it with a bottom-up method: build the world as encountered in the narrative, then piece together the broader world that emerges from these details. Many writers fall somewhere in between, using a bit of both methods (much like writers on the plotting-pantsing spectrum).

Top-down world-building

Far from what it’s name suggests, the top-down process does not imply spending all your time building your world in great detail before writing. Rather, in the spirit of the top-down design principle (also called “stepwise design”), this process involves gradually breaking down a system to gain insight into how it’s sub-components work. Applying this to world-building, a writer starts at the most important, all-embracing part of the system–the world of the story–and breaks that down:

A story world consists of broad categories: people, places, things. Each of these in turn can be broken up into finer categories. People, for example, can be broken up into races, culture, social organization, religion, cosmology, arts, language, and history; this part often can include language dictionaries, family trees, and comparative chronologies. Places can be broken up into geography, nations, flora and fauna, ecology, and climate; this part often can include maps. Things can be broken down into tools, inventions, items, foods, medicines, magic, technology, etc. I should note that this way of breaking down the categories is just one way of looking at it–you can search the web to find many categorical guides for top-down world-building which organize sub-components differently, just as long as the logic makes sense to you!

An important point here is that with top-down world-building, the goal is not to rigorously develop every sub-system, then develop every sub-subsystem of every sub-system, ad infinitum. Rather, the goal is to lay out the groundwork for the existence of relevant sub-systems and create placeholders for information as it emerges (in top-down design terminology, these are called “black boxes”). What this means is the world-builder acknowledges that the scope of world-building is infinite, and so rather than trying to rigorously map out every single category and sub-category, and so on, the goal is to properly define what each category and sub-category is and be able to add to and modify it as development continues.

Bottom-up world-building

Some writers just need to write in order to discover story (myself included), which means the bottom-up method often works better for them. In this method, the most specific elements of the world enter the story and the writer develops a way to collect and organize the information as its encountered, with the goal of analyzing and developing the world to make sure it’s cohesive as it’s coming together.

This is especially helpful for writers who are susceptible to “world builders disease” — a termed coined by the Writing Excuses podcast back in Season 3: episode 1 to describe the “symptom” when none of the writing you’re working on is going to appear in your novel. There’s nothing wrong with this if your primary goal is world-building; one writer who I know world-builds as a hobby but says he finds all his stories from the world-building process, which he devotes time to writing down separately. But for many writers this tendency to fall into the endless abyss that is world-building can be problematic.

The bottom-up method is a useful way of making sure that readers can still encounter an internally consistent and cohesive world, since building as you go can lead to flaws and contradictions or poorly-thought-out schematics, such as a large city in the desert (non-modern times) or rivers the branch downstream.

These are all avoidable with a proper bottom-up world-building method, so it’s not necessary to build in great detail the entirety of a world to give the sense to a reader that they’re only seeing 10% of it in the story. George R. R. Martin, for example, is a bottom-up world-builder who admits, in an interview, that he writes down and charts very little, keeping it all in his head and making up what he needs as it’s relevant to the story. And anyone familiar with his work would no doubt agree that the world-building which presents in his world is highly detailed and feels much larger than the mere narrative that moves a reader through it.

Blood Dawn: An example of a hybrid bottom-up world-building in process

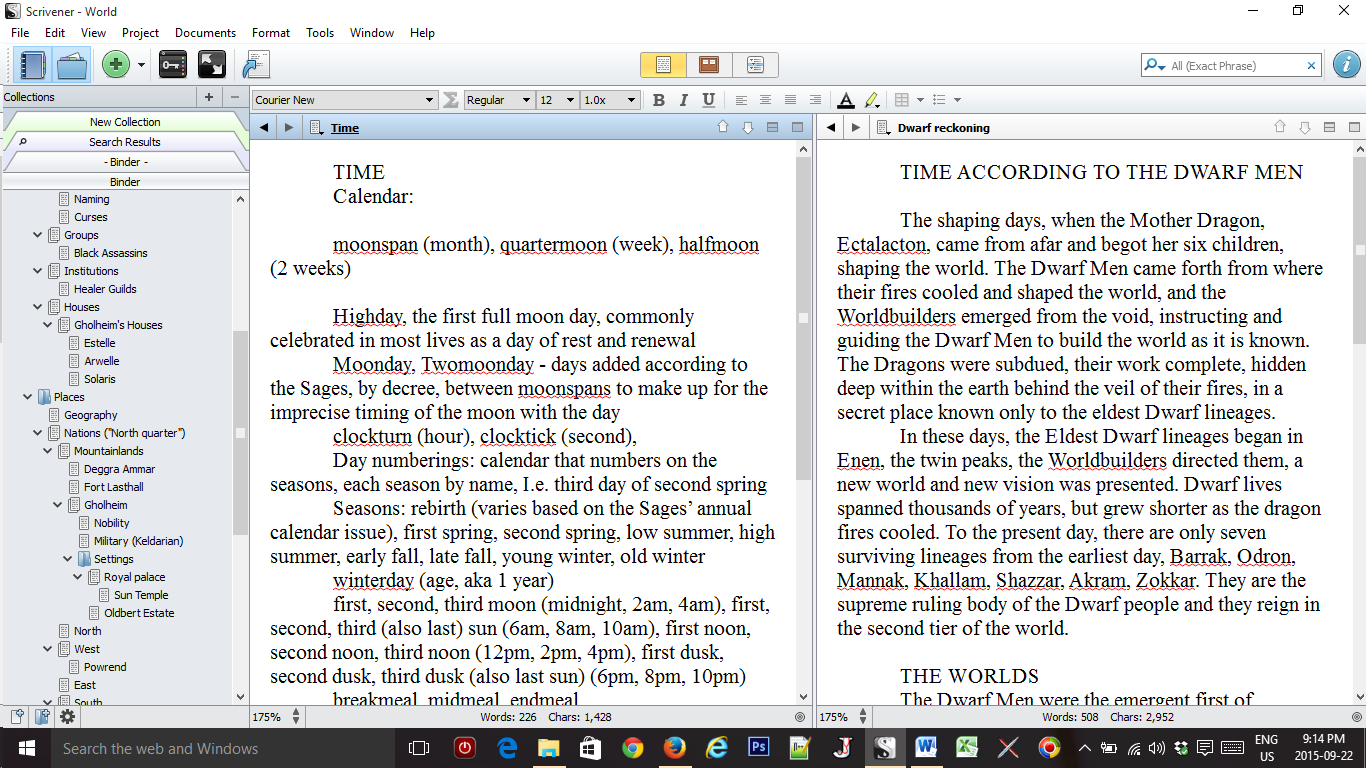

A screen capture of my world building notes. You’ll see on the left, I have my menu showing all the different notes. On the right I am using split screen so I can keep two different notes open at the same time.

To illustrate this in example, I am a bottom-up world-builder, with maybe about 20% top-down in my process. For my epic fantasy Blood Dawn, whose first draft I wrote between 2014-2015, I created a topic tree (shown above) as I went along and collected / developed relevant world-building information as it came up in the story. Initially, I had notes just for character and setting, but these were soon replaced with a separate category I labelled “world”, itself broken up into the relevant aspects of world-building which emerged from developing deeper levels of character and setting through the insight gained during the drafting process. Soon, I had history, culture, nations, languages, etc, and it continued to develop from there. The “top-down” in my process involved the creation of categories and occasional stints into fleshing them out as black boxes to further develop other relevant parts of the world; many of these were built from an already existing world that I’d been developing for the last twenty years.

As mentioned above, the key to making bottom-up world-building work is to make sure you have a bottom-up system. This is just one example of a system. Every writer will develop their own system that works. What matters is that there is a way to question and explore related details in each setting and for each character so that the story world is cohesive.

I hope you enjoyed this post and learned something about world-building in the process. As a fantasy writer, where do you align? Top-down? Bottom-up? A hybrid of the two?

Look forward to more posts on world-building and what makes a fantasy setting rich, detailed, believable and immersive.

As a fantasy writer, I definitely fall more into the camp of “top-down” worldbuilding. Just like how I’m a solid 6.5 on the Richard Dawkins scale of Theistic Probability, I’m probably about 95% top-down worldbuilder. Simply put, I find it so much easier to generate stories and plot points once I know the details of a world and how its myriad parts interact with one another to form a living tapestry.

So happy you chimed in — actually, it was your method of finding stories from the top-down process of world building that I referenced in my post. I have to say you’ve tipped me more in the top-down direction from our correspondence — especially showing me how to make a wiki. Say, we owe the EFW crowd another installment of World Builders 3.0, don’t we 😉

I think we do. That’ll be coming up soon, I hope. 😀

‘Tis the season!

Very nice. A fine laying out of methods and terminology, indicating an in-depth study of the information.

I’m definitely more of a bottom-upper myself. Everything about my story, character and plot-wise, is in my head, except for some very skeletal outlining I did at one point.

Thanks for sharing, Sean! We’re kindred spirits in this regard I think. Love what you say about how character and plot live in your head. Really, when we go in and map out story, even with a top-down process, the story and its elements live in some infinite space that is so much larger than anything we can cover comprehensively. The only way to bring story to life is to write, daringly, bravely–and really, when it comes to methods, its about learning what produces the best results. Happy writing!

Reblogged this on Archer's Aim and commented:

I think the plot governs what the fantasy world should be. That and a good map! The details enhance the story with twists, adventure and everything else.

Thanks for this! I think you’ll enjoy our next one, coming soon, since it’s on building world for plot 😉

I’m happy to share!

Pingback: Writing Links in the 3s and 5…11/21/16 – Where Genres Collide